Joseline Cano

Co- Editor- in-Chief

canojose@my.dom.edu

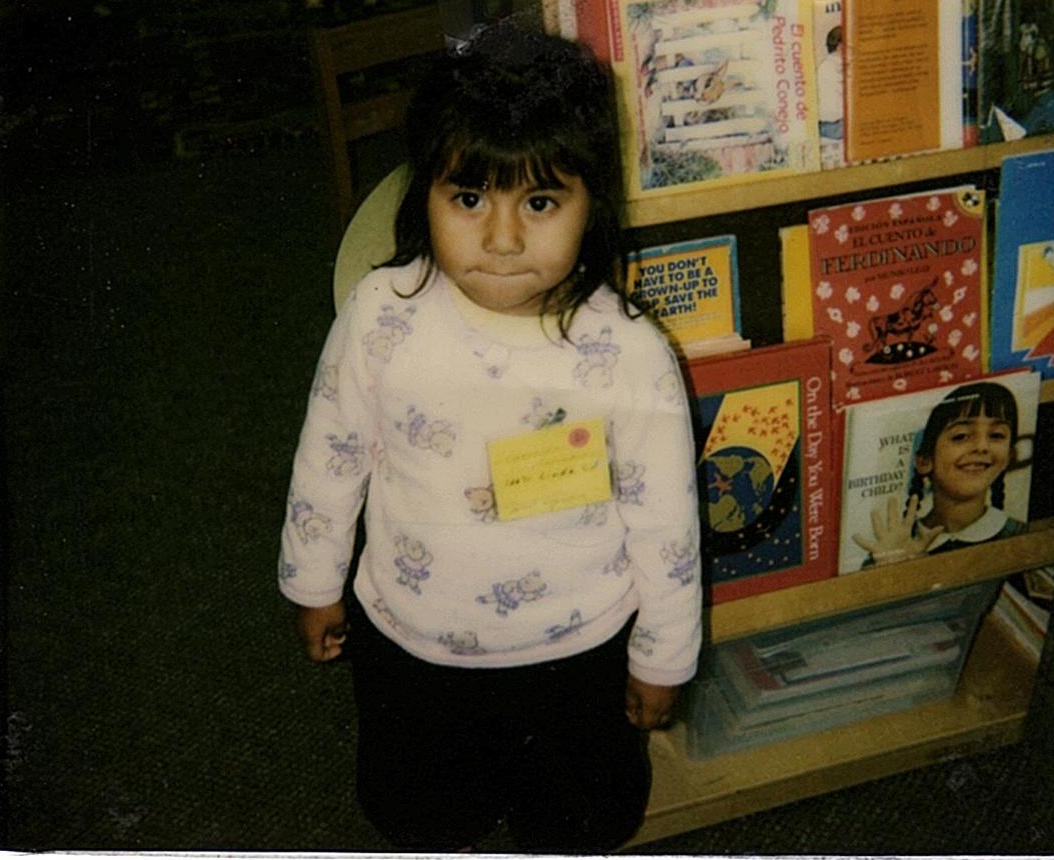

Esmeralda Montesinos was 2 years old when she and her mother were abandoned in a desert in Sonora, Mexico. Her dad, who was waiting for them in Arizona, had been in the United States for a few months working to support his family. He had been saving up to pay a coyote, a person who smuggles in people to a country. The coyote had scammed him of his money and left his wife and daughter miles away from where they needed to be. This desert is where Esmeralda, her mother, and countless other migrants made their journey to reach the United States.

Montesinos recalls nothing from that experience.

“My mom says it was really hot and hard,” she says, the regular temperature in this area of the state reaches 104 degrees Fahrenheit. “People were being captured and detained on the way there but we made it and crossed the border through Arizona. Once we made it, we were able to board a plane which lead us to Illinois. This is where I essentially started my life.”

Montesinos and her parents first settled in a small apartment with three other people in Des Plaines. Her parents would force her to watch TV in English in hopes of her being able to pick up on the language. She started off school being placed in bilingual classes which were meant to help her transition into a full English environment, yet, when this transition occurred, she still found it difficult to fully communicate.

As she continued to strive to be educated, her mother gave birth to a son, whom became the only member in the family with legal status. With a growing family, they first decided to move to Joliet, where they lived in a three-bedroom house with an additional eight people. The family eventually got tired of the over-crowdedness, saved money from both parents working all day, and moved to a separate house in a nicer side of the neighborhood.

Despite finally having a home to themselves, an even bigger struggle followed.

“I had grown up in a predominantly Hispanic area. Now I was living in a neighborhood where I was one of the only non-white students at my school. I was culture shocked. I didn’t talk to anyone. This was all happening during the Bush era and all I kept seeing on TV was people being dragged out of their houses in handcuffs because they were undocumented. I felt like my family was unsafe there.”

What Montesinos didn’t know is that her parents weren’t the only ones facing deportation. Montesinos did not know she was undocumented until her sophomore year of high school. She had grown up knowing her parents did not have legal papers to be in the country, but she had always assumed she did because the United States is the only home she can remember.

“I was asked for my Social Security number for my drivers ed class,” she said, “I asked, ‘Mom, where is this?’ and she said, ‘You don’t have one’. What does she mean I don’t have a social Security Number? She sat down and explained it to me.”

Luckily, around the time she made this discovery, President Barack Obama had announced a program that would protect undocumented people who were brought into the country at a young age and provide them with a state ID, temporary protection from deportation, and a work permit. On June 15, 2012, DACA was signed into action. Montesinos applied and

was granted the opportunity to join in on her classmates joy of obtaining a license. “Junior and senior year were the highlights of my life. For the first time, I felt a sense of protection and belonging.”

This feeling lasted until November 21, 2016. The TV screen in her living room read, ‘Donald Trump is the 45th President of the United States.’ Montesinos and her brother stayed up all night to watch the results, not wanting to have to wait until the morning to know where her future was heading. Sha recalls it being one of the very few times she broke down and cried alongside her brother, who was equally as afraid as she was about how his family would handle the next four years. Up until that point, Montesinos’ life had consisted of her working three jobs, being a full time third-year student, and engaging in events and clubs Dominican has. Now it was a constant worry of when she’d have to give up her life in the US if Trump decided to rescind DACA.

On September 5, 2017, President Trump sent Attorney General Jeff Session to announce the end of the program halting the lives of more than 800,000 people in the country.

Montesinos was working when the news broke. She didn’t allow herself the chance to read the decision until after, when she sat in her car.

“As I was reading it, I got angrier and angrier at his word usage and the way we were being painted. ‘The law’ this, ‘the law’ that. Why are you saying laws are more important than human beings?” she says.

“My parents came here to give me a better life. The cartels in Mexico and the corrupt government is what pushed them here. We were in literal poverty in Mexico. We didn’t have anything. All they want is to give me a better life. That is what has essentially made me who I am. I feel like this is a shared experience between all DACA recipients. I have not met a single DACA recipient that does not feel empowered and motivated by the sacrifices our parents made,” she said, “I haven’t met a single one that isn’t good in school, or not active in social issues and sports. I haven’t met a single one that isn’t smart.”

Upon getting home that day, Montesinos informed her mom about the choice President Trump had made. Her mother reassured her that she would be fine, and it wasn’t until she made it to her room where she let herself be overcome with the grief she was feeling. She says, “As the oldest child, as first in the family, as the DACA recipient, you have this need to stay strong for your family, this need to not look weak in front of your family. If you can’t handle it, how can they? That’s how I view it.”

Now, as Montesinos awaits an unpredictable future, she remains positive.

“This time around, I feel more inspired, I feel stronger, and I feel hopeful. El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido. We have to do this together.”